GPU Parallel Reduction: Algorithm and Optimization Strategies

Introduction

Parallel reduction is a fundamental GPU algorithm that demonstrates the hierarchical nature of GPU architecture: warp-level operations, block-level synchronization, and grid-level coordination.

This post explains the reduction algorithm and benchmarks three implementation strategies with different vectorization widths (int, int2, int4).

The benchmark code is available in this repository.

Reduction Algorithm

The figure below illustrates a parallel sum reduction across two thread blocks (simplified to block size 16 and warp size 8 for visualization):

The algorithm proceeds in five steps:

- Warp-level reduction: Each warp reduces its values using warp-level primitives (no memory required)

- Warp leaders write to shared memory: Lane 0 of each warp stores its partial sum to shared memory

- Block-level reduction: Warp 0 in each block reduces the warp partial sums from shared memory

- Block leaders write to global memory: Thread 0 of each block stores the block’s partial sum

- Final reduction: A second kernel reduces all block sums to produce the final result

This hierarchy maps directly to GPU hardware: shuffle instructions operate within warps, shared memory enables block-level communication, and global memory coordinates across the entire grid.

Implementation

The reduction is built from three device functions:

Thread-level accumulation:

Each thread accumulates values from global memory using a grid-stride loop. This pattern ensures good load balancing and allows the kernel to handle arbitrary array sizes with a fixed grid configuration.

template<>

__inline__ __device__

int ThreadAccumulate<int>(const int* __restrict__ input, int num_elements)

{

int idx = blockIdx.x * blockDim.x + threadIdx.x;

int sum = 0;

// Grid-stride loop

for (int i = idx; i < num_elements; i += blockDim.x * gridDim.x)

{

sum += input[i];

}

return sum;

}

Warp-level reduction using shuffle:

After each thread has its partial sum, warps reduce their 32 values using __shfl_down_sync. This operates entirely in registers without memory access, making it extremely efficient.

__inline__ __device__

int WarpReduce(int val)

{

constexpr unsigned int mask = 0xFFFFFFFF;

#pragma unroll

for (int offset = warpSize/2; offset > 0; offset /= 2)

{

val += __shfl_down_sync(mask, val, offset);

}

return val;

}

Block-level reduction combining warp shuffle and shared memory:

Each warp produces one value via WarpReduce. These warp results are written to shared memory, then warp 0 performs a final reduction across all warp sums to produce the block’s result. Since CUDA allows a maximum of 32 warps per block, a single warp is sufficient for this final step.

__inline__ __device__

int BlockReduce(int val)

{

int lane = threadIdx.x % 32;

int wid = threadIdx.x / 32;

val = WarpReduce(val);

static __shared__ int smem[32];

if (lane == 0) smem[wid] = val;

__syncthreads();

val = (threadIdx.x < blockDim.x/warpSize) ? smem[lane] : 0;

if (wid == 0) val = WarpReduce(val);

return val;

}

Putting it all together:

These three device functions combine to form the reduction kernel:

template<typename VecType>

__global__

void ReduceKernel(const int* __restrict__ input, int* __restrict__ output, int num_elements)

{

int sum = ThreadAccumulate<VecType>(input, num_elements);

sum = BlockReduce(sum);

if (threadIdx.x == 0) output[blockIdx.x] = sum;

}

Each thread accumulates values from global memory, threads within each block reduce to a single value, and block leaders write their results to global memory for the final reduction pass.

Optimization Strategies

Vectorized Memory Access

To improve memory bandwidth, ThreadAccumulate can be templated to use wider vector loads:

template<>

__inline__ __device__

int ThreadAccumulate<int2>(const int* __restrict__ input, int num_elements)

{

int idx = blockIdx.x * blockDim.x + threadIdx.x;

const int2* input2 = reinterpret_cast<const int2*>(input);

int sum = 0;

// Grid-stride loop with 8-byte vectorized loads

for (int i = idx; i < num_elements / 2; i += blockDim.x * gridDim.x)

{

int2 val = input2[i];

sum += val.x + val.y;

}

// Handle tail elements

int i = idx + num_elements / 2 * 2;

if (i < num_elements) sum += input[i];

return sum;

}

The same pattern extends to int4 (16-byte loads) for maximum bandwidth.

Three Reduction Strategies

TwoPass: Traditional two-kernel approach following the algorithm diagram (Step 5). Each block writes its partial sum to global memory, then a second kernel launch with a grid size of one, reduces these values.

BlockAtomic: Single kernel using shared memory and block-level atomics. Thread 0 of each block atomically adds its result to global memory, eliminating the second kernel launch.

WarpAtomic: Single kernel that skips shared memory and block-level reduction entirely. Lane 0 of each warp atomically adds its result directly, avoiding synchronization overhead.

Results and Discussion

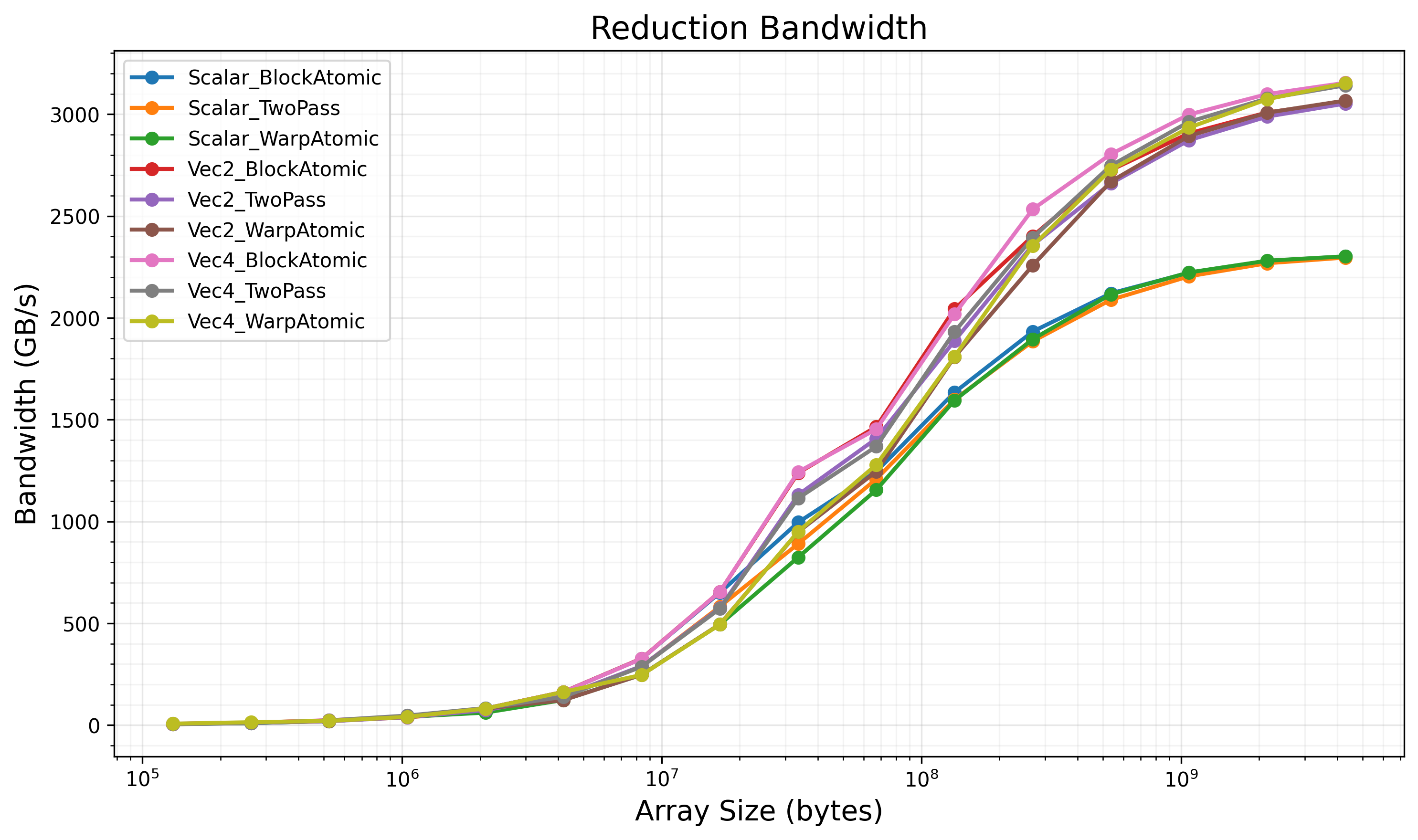

The benchmark evaluates all three strategies with scalar (int), 2-element (int2), and 4-element (int4) vectorized loads on H100 (block size = 512, grid size = 1024).

All kernels reach stable HBM bandwidth:

Vec4 variants (16-byte loads):

- All strategies: ~3100-3200 GB/s

Vec2 variants (8-byte loads):

- All strategies: ~3000-3100 GB/s

Scalar variants (4-byte loads):

- All strategies: ~2300 GB/s

The Vec4 variants achieve approximately 92-95% of H100’s theoretical peak bandwidth (3.35 TB/s), which is typical for memory-bound workloads.

Key observations:

Vectorization has the dominant impact on bandwidth. Vec4 consistently outperforms Vec2 and scalar variants regardless of reduction strategy.

All three strategies achieve similar peak bandwidth for the same loading vector width. However, Vec4_BlockAtomic achieves the best overall performance as it eliminates the second kernel launch while maintaining lower atomic contention compared to warp-level atomics.

Conclusion

For memory-bound reduction kernels:

Vectorization is critical. Use 8- or 16-byte vector loads (int2, int4) when data alignment permits. This provides the largest performance gain across all array sizes.

Reduction strategy choice matters. While TwoPass, BlockAtomic, and WarpAtomic achieve similar peak bandwidth for the same vector width, BlockAtomic delivers the best overall performance across intermediate array sizes, followed by TwoPass. WarpAtomic adds atomic contention overhead that degrades performance until arrays are large enough to reach peak bandwidth.

The hierarchical nature of GPU reduction—warp shuffle, block shared memory, grid global memory—efficiently maps to hardware and delivers bandwidth within 5-10% of theoretical peak.